Abstract

This mini-essay examines boundary layer separation in fluid dynamics, a critical phenomenon that occurs when the boundary layer detaches from a surface due to adverse pressure gradients. The study explores the fundamental mechanisms behind separation, including the role of viscosity in retarding fluid momentum and the influence of pressure distribution on boundary layer behavior. Through practical examples from Formula 1 vehicles and aircraft, the essay demonstrates how separation leads to form drag and performance degradation. The analysis compares laminar and turbulent boundary layer separation characteristics, showing that turbulent flows are more resistant to separation. The essay discusses separation in various geometries including circular cylinders and diffusers, and examines the formation of unsteady wakes and vortex streets. Several methods for preventing separation are presented, including boundary layer suction, tangential blowing, and the use of slats. The work emphasizes that while separation is generally undesirable due to energy losses, understanding and controlling this phenomenon is essential for optimizing aerodynamic performance in engineering applications.

Key words

Boundary layer

The thin region of fluid adjacent to a solid surface where viscous effects are significant and velocity transitions from zero at the wall to the free stream velocity.

Adverse pressure gradient

A condition where pressure increases in the direction of flow, opposing the fluid motion and potentially causing boundary layer separation.

Favorable pressure gradient

A condition where pressure decreases in the direction of the flow, helping to maintain boundary layer attachment to the surface.

Form drag

The component of drag force resulting from pressure differences between the front and rear of a body, typically increased by boundary layer separation and wake formation.

Separation point

The location on a surface where the boundary layer detaches, characterized by zero wall shear stress and zero velocity gradient at the wall.

Laminar boundary layer

A boundary layer flow characterized by a smooth, ordered fluid motion in parallel layers with minimal mixing between layers.

Turbulent boundary layer

A boundary layer flow characterized by chaotic, irregular fluid motion with significant mixing, generally more resistant to separation than laminar flow.

Dead water

The region of separated flow behind a bluff body where re-circulation occurs, contributing to increased form drag.

Karman vortex street

A regular pattern of alternating vortices shed from a body in cross-flow, creating an unsteady wake structure.

Boundary layer suction

A flow control technique where slow-moving boundary layer fluid is removed through slots or porous surfaces to prevent separation.

Boundary layer separation

In fluid dynamics, one of the most important things to understand is the concept of “boundary layer,” which explains how the flow remains attached to the surface of a body. This concept is super important as it is what allow humans to do the impossible: to fly, to go faster in road vehicles, or even in heat exchangers to maintain the optimum temperature. Hence, naturally it comes to our minds what would happen if the boundary layer detaches from the surface and how this phenomenon is produced.

To understand the importance of the boundary layer separation and how it might affect the performance, let’s imagine the next example. Consider a Formula One vehicle; this car should remain attached to the ground for better cornering; so, engineers achieve this by making it to produce downforce (which is the contrary of lift) mainly through Bernoulli’s Principle, hence, the airflow beneath the car (through the floor) travels faster and with lower pressure than the flow above. When airflow reaches the diffuser, the geometry expands, this sudden expansion can lead to flow separation—and not just for the expansion, but also for the adverse pressure gradient; hence pressure goes from lower to greater (and not from greater to lower as normal, ). So, a separation of the boundary layer from the body and the formation of large or small eddies at the back of the body can then occur, leading to the form or pressure drag of the body [1], leading as well to a great decrease of performance, which traduces to a loss in championship points, which traduces to a loss of money at the end. Another example, and clearly more several, is the boundary layer separation of a plane airfoil, which immediately makes the aircraft to stall and that may result in a big tragedy; therefore, the process involved in maximum lift of an airfoil can only be understood using boundary-layer theory.

Understanding boundary layer separation

Now that we know its importance and how it may affect performance, the next step is to understand why this is originated. Let’s remind that the action of viscosity (the resistance of a fluid to motion) in the phenomenon of fluid motion past a surface is to retard the velocity and consequently decrease the fluid momentum within the boundary layer [2]. Although the retarding action of viscosity is dominant only near the surface, it exerts a very strong influence on the overall flow behavior past the surface. In the same way, we need to remind that pressure gradient is what creates a net force causing the flow to move in some direction, naturally going from greater pressure to lower pressure (pressure is a scalar quantity, not a vector. Imagine we have a closed container with a pressurized gas, if we measure the pressure at its walls, we will realize it’s the same at each one of them, this is due to pressure acting at every direction. Therefore, we can imagine flow as a pressure pushing the particles of the fluid towards a specific direction ()).

Now that we know that fluid flow is governed by the pressure distribution impressed on the boundary layer, we must take into consideration the retarding action of viscosity and the imposed pressure distribution. Now if the pressure distribution is such that decreases along the direction of the fluid flow, then the boundary layer will remain attached to the surface. On the other hand, if there is a pressure increase in the direction of the main flow, then—due to the reduced fluid momentum—the boundary layer cannot remain attached to the surface [2]. Once separation has taken place, the vorticity—which was originally confined within the boundary layer—finds its way into the outside streaming flow, disturbing the outer flow. Separation causes the formation of wake behind the body, which causes a rise in the overall drag of the body (known as “form drag”).

In summarize, when the flow in the inviscid outer the flow region (outside the boundary layer) accelerates, velocity increases and pressure decreases. This is the favorable pressure gradient; and it is favorable as the boundary layer is usually thin, very close to the wall, and it is not likely to separate from it. When the outer flow decelerates, velocity decreases and pressure increases; therefore, we have a unfavorable or adverse pressure gradient. This is not desirable because the boundary layer us usually thicker, does not hug closely to the wall and it is much more likely to separate from it.

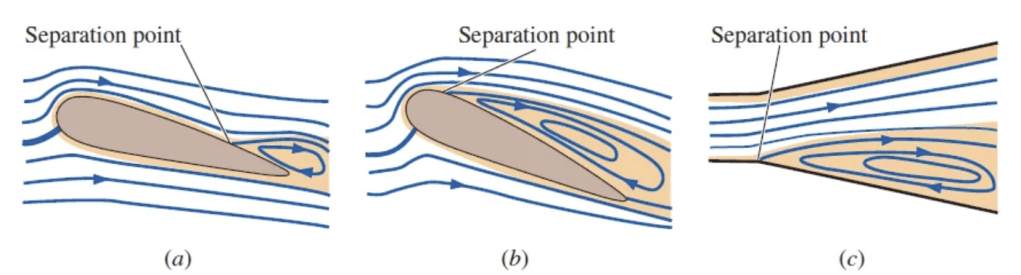

In a typical external flow, like over a airplane wing, the boundary layer in the front portion of the body is subjected to a favorable pressure gradient, while in the rear portion is subjected to an adverse pressure gradient. If the adverse pressure gradient is strong enough the boundary layer is likely to separate off the wall [3]. The boundary layer remains attached over the entire lower surface of the airfoil, but it separates somewhere near the rear of the upper surface. In figure 1 we can see closed streamlines indicating a region or recirculating flow called a “separation bubble.” Separation leads to reverse flow near the wall, destroying the parabolic natura of the flow field, and rendering the boundary layer equation inapplicable.

On the other hand, turbulent boundary layers have qualitatively similar behavior, although the mean velocity profile of a turbulent boundary layer is much fuller than a laminar boundary layer under similar conditions. Thus a stronger adverse pressure gradient is required to separate a turbulent boundary layer. Therefore we can say that: Turbulent boundary layers are more resistant to flow separation than are laminar boundary layers exposed to the same adverse pressure gradient [3].

A more detailed and visual way

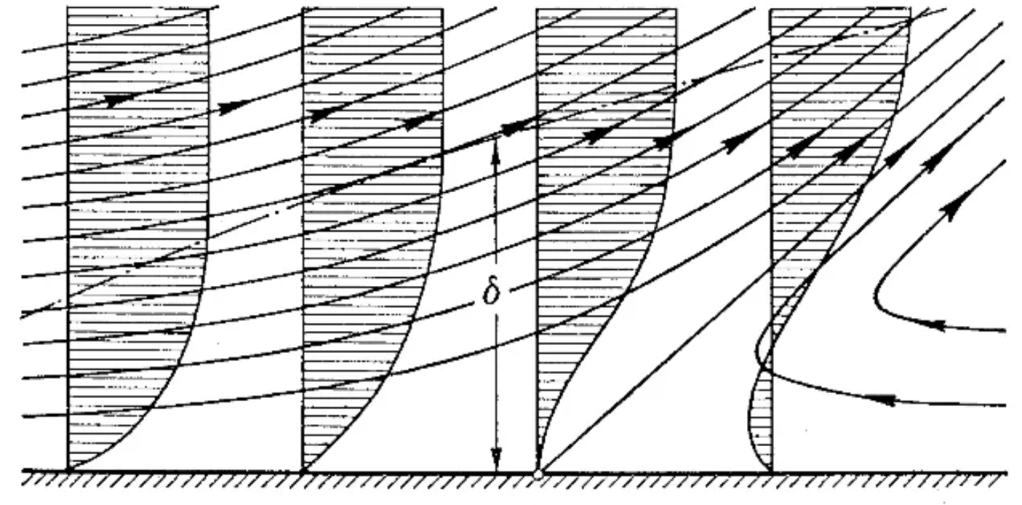

Now that we understand the basics, let us consider the flow past a circular cylinder (figure 2). In a inviscid symmetric flow, an accelerated flow with pressure drop is present on the front half from D to E; from E to F on the back there is a decelerated flow with pressure increase. Then, after setting the flow in motion, as long as the boundary layer remains very thin, an almost inviscid flow first forms. For a particle in the outer flow moving from D to E, pressure is transformed into kinetic energy, and moving from E to F, kinetic energy is transformed into pressure. A fluid particle directly at the wall in the boundary layer is also acted on by the same pressure distribution as in the outer flow, since this is imposed on the boundary layer [4].

Because of the strong friction forces in the thin frictional layer (viscosity), a boundary layer particle loses so much of its kinetic energy that it cannot manage to get over the “pressure mountain” from E to F. such particle cannot make much headway into the region of increasing pressure from E to F. It comes to a standstill, and is pushed backwards into motion by the pressure distribution of the outer flow. We can observe clearly in figure 2 how the pressure increases along the contour of the body from left to right.

Separation condition

As a clear takeaway we can agree that there is always danger of separation in regions where the pressure increases, and it is even greater the larger the increase, particularly for bodies with blunt rear sides. Moreover, the position of separation (the certain angle with which the streamlines leave the wall) is given by the condition that the velocity gradient perpendicular to the wall vanishes at the wall; therefore, the wall shear stress vanishes () [4].

Also, it is important to consider that flow separation is frequently quite sensitive to small changes in the shape of the body, particularly if the pressure distribution is strongly affected by the change of shape of the body.

Separation in diffusers

Just as in cylinders, the same process occurs in a channel which widens in the direction of flow (a diffuser). Up until the narrowest section the pressure drops in the direction of flow, and here the flow right along the walls is inviscid. After the narrowest point, the expansion is so great and therefore the pressure increase so large that the boundary layer separates from both walls. The flow now only fills a small part of the cross-section of the channel. However, if the boundary layer is sucked away at the walls, the separation comes to a stop (what Formula One diffusers do) [4].

Separation and lift/drag coefficients

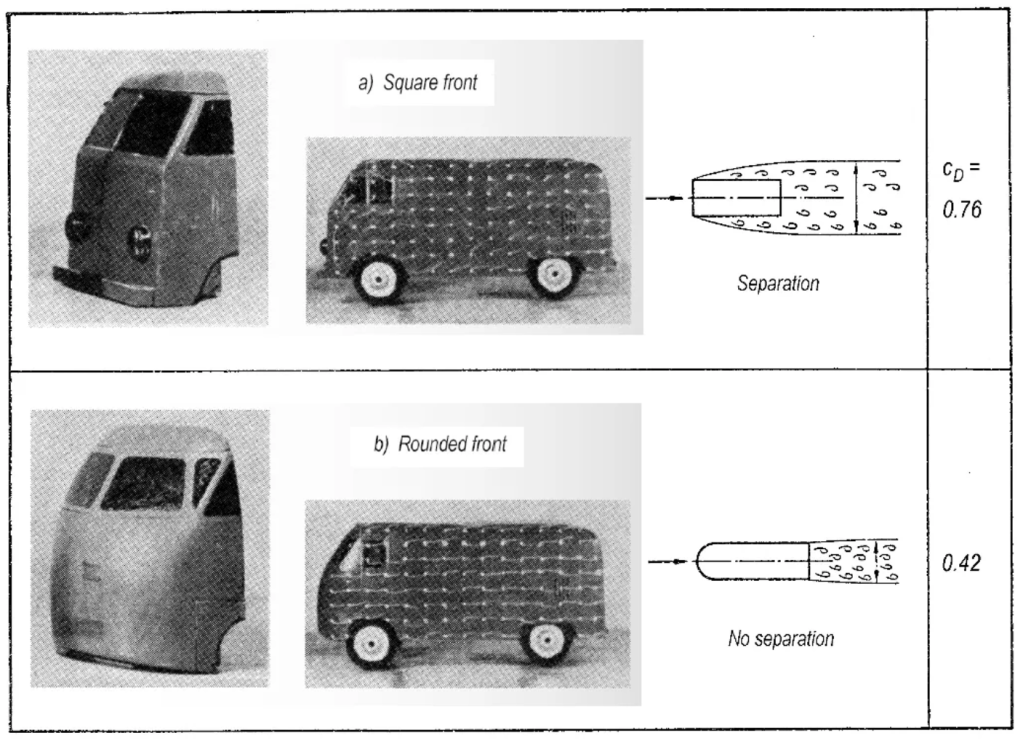

An instructive example is to be found in the flow portraits of the model of a motor vehicle (a VW-van). If the front of the van is square, the flow past the sharp front edge produces strong negative pressures and therefore a strong increase in pressure along the side walls, leading to a complete separation of the boundary layer along the whole side wall and a large “dead water” behind the body. The drag coefficient for this square van is . However, for a rounded front, the strong negative pressures at the front edge are avoided and a flow attached to the entire side wall is achieved. So there is a considerable reduction in the drag coefficient to

[4].

Separation is also important in the production of lift of an airfoil. At small angles of attack (up to 10°), the flow moves along both sides without separation [4]. As angle of attack is increased (about 15°), there is danger of separation on the suction side; this because pressure increase is greater here, the inviscid lift-producing flow has been destroyed and the drag is very high now. Approximately, the start of separation coincides with the maximum lift of the airfoil.

Now, if flow close to the speed of sound is considered, a shock generally forms on the suction side of the airfoil. If the shock is strong enough, the pressure distribution it causes can lead the boundary layer to separate. Because the additional form drag occurring, a drastic increase of the drag can take place close to the speed of sound; this is frequently called the “sound barrier.”

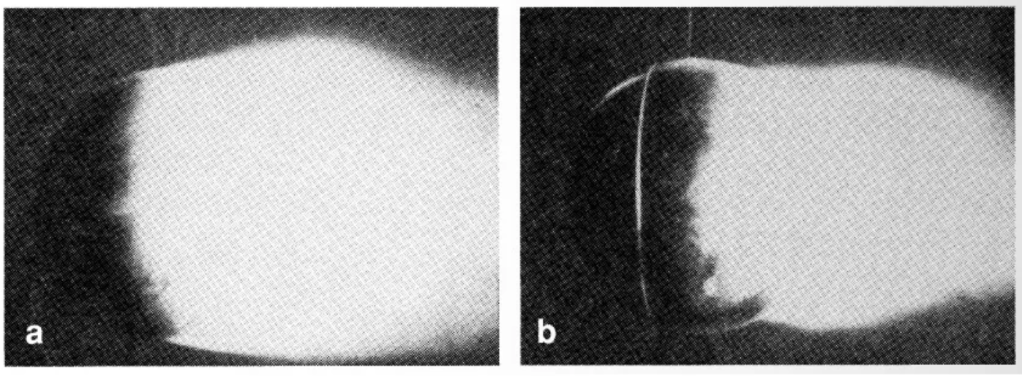

Difference between laminar and turbulent boundary-layer separation

A laminar-turbulent transition in boundary layers occurs at blunt bodies (such as in cylinders and spheres), also, a sudden large drop in the drag coefficient takes place. The point of separation thus is moved further backwards, because of the turbulent mixing motion, the energizing action of the outer flow on the turbulent boundary layer is much greater than in the laminar case. The separation point for laminar flow lies approximately at the equator, but when the boundary layer becomes turbulent, the point is moved some distance downstream. Thus the “dead water” are behind the body becomes considerably narrower, and the pressure distribution becomes closer to that inviscid flow [4].

And this is super interesting because, as the dead water area shrinks, a considerable lessening of the form drag takes place. Prandtl was able to show that, by placing a thin wire ring around the sphere just in front of the equator (figure 5), this artificially makes the laminar flow turbulent at a lower Reynolds number, and the same drop in drag which normally only happens at higher Reynolds numbers.

It is important to note that separation can in general only be prevented if the flow in the boundary layer is turbulent. A laminar boundary layer can tolerate only an extremely small pressure rise, so that separation occurs even if the body is very slender. This is particularly true even for airfoil flow with a pressure distribution, where the risk of separation is larger on the suction side. However, here too, a smooth, separation-free, lift-producing flow is only possible if the boundary layer flow is turbulent.

This can be summarized by saying that both the small drag of slender bodies as well as the lift airfoils are generally due to the turbulence in the boundary layer.

Unsteady wakes

In spite of steady free stream conditions, the flow after separation is in no way steady. By this it means varying processes in the mean motion, which move slowly compared to any turbulent fluctuating processes. Sometimes a regular arrangement of vortices rotating clockwise and anticlockwise appears behind the body (known as the Karman vortex street). The unsteady character of the wake clearly has a great effect on the drag if the body.

Measures to prevent separation

The separation of the boundary layer is generally undesirable, since it leads to great losses in energy. Certain measures have been devised to artificially prevent separation of the boundary layer.

It is physically easiest to move the wall in the flow direction too and thus to remoce the velocity difference between wall and outer flow, the origin of boundary layer formation. Of course, technically this is very difficult to realize.

Another useful method to prevent boundary layer separation is suction. The slowed boundary layer material is sucked into the inside of the body through narrow slits on the wall. If the suction is strong enough, boundary layer separation can be prevented. Suction has been used effectively to increase the lift on airfoils too. Applied to the back of the upper side, suction can be used to keep the flow along side the airfoil at much larger angles of attack than otherwise. This leads to a considerable increase in the maximum lift.

Separation of the boundary layer can also be prevented by blowing tangentially into the boundary layer. Using a “wall jet” blown through a slit on the contour of the boundary layer parallel to the main flow direction, the boundary layer can be given enough kinetic energy to prevent separation. The maximum lift can be considerably increased using this principle.

Finally, a slat can be used on airfoils to prevent separation. In this case the pressure distribution on the airfoil is suitably influenced by the pressure of the slat. Positive pressure gradients are avoided and thus separation prevented.

Conclusions

Boundary layer separation represents one of the most significant challenges in fluid dynamics, with far-reaching implications for aerodynamic performance across various engineering applications. The phenomenon occurs when adverse pressure gradients overcome the momentum of boundary layer fluid, leading to flow detachment and the formation of energy-dissipating wakes. Understanding that turbulent boundary layers are inherently more resistant to separation than laminar ones provides crucial insight for flow control strategies. The practical consequences of separation—from reduced downforce in Formula 1 cars to stall conditions in aircraft—underscore the importance of managing pressure distributions and boundary layer characteristics. While separation is generally detrimental to performance, the availability of control methods such as suction, blowing, and geometric modifications offers engineers tools to mitigate these effects. Ultimately, the mastery of boundary layer separation principles is essential for optimizing fluid dynamic systems, whether in aerospace applications where separation can mean the difference between flight and catastrophe, or in automotive design where it directly impacts performance and efficiency.

Sources of information

[1] Boundary-Layer Theory (p. XXII) – Hermann Schlichting, Klaus Gersten

[2] Handbook of Fluid Dynamics (p. 10-13) – Richard W. Johnson

[3] Fluid Mechanics Fundamentals (p. 583) – Yunus A. Cengel, John M. Cimbala

[4] Boundary-Layer Theory (p. 39-48) – Hermann Schlichting, Klaus Gersten