Abstract

The concept of the boundary layer is central to understanding fluid flow near solid surfaces. This mini-essay introduces the distinction between ideal and real fluids, highlighting how viscosity, absent in ideal fluids, becomes essential in describing the behavior of real fluids in contact with walls. The no-slip condition explains the development of a boundary layer, where fluid velocity transitions from zero at the wall to the free stream value. Concepts such as viscosity, shear, and the Reynolds number are explored as key to defining laminar and turbulent flow. The essay also covers how velocity profiles evolve inside pipes and across flat plates, culminating in the fully developed region. This descriptive investigation highlights the importance of the boundary layer in fluid mechanics, especially in high Reynolds number flows such as air and water.

Key words

Fluid mechanics

Branch of physics that studies the behavior of fluids under the influence of forces.

Viscosity

A physical property of fluids representing internal resistance to deformation or motion, responsible for generating friction between fluid layers.

Reynolds number

A dimensionless quantity that compares inertial forces to viscous forces in a flow, used to predict whether a flow is laminar or turbulent.

No slip condition

The assumption that the velocity of a fluid in contact with a solid surface is equal to the velocity of the surface itself—typically zero for stationary walls.

Inviscid

It refers to an idealized fluid that has no viscosity, i.e. does not resist shear stress and offers no internal friction between fluid layers.

Laminar flow

A smooth orderly fluid motion characterized by parallel streamlines and low Reynolds number, where viscous forces dominate.

Turbulent flow

A chaotic, fluctuating motion of a fluid occurring at high Reynolds numbers where inertial forces dominate and eddies mix momentum.

Fully developed flow

A region in a pipe or channel where the velocity profile no longer changes in the flow direction, and the effects of viscosity have stabilized.

Velocity gradient

The rate at which fluid velocity changes with distance from the wall, central to defining shear stress within the boundary layer.

Tangential forces

The forces that act parallel to a surface or between adjacent fluid layers. This is associated with viscosity and is responsible for shear stress within the fluid.

Understanding the boundary layer concept

When analyzing fluid mechanics, theoretical investigations are based on 2 type of fluids, the ideal and the real ones [1]. The ideal ones are inviscid and incompressible. In the inviscid fluids, no tangential forces (shear stresses) exist between adjacent layers, only normal forces (pressures); i.e. an ideal fluid does not oppose a change in its shape with any internal resistance. However, this theory is useless when faced with the problem of calculating the drag of a body—as it would state that there is no drag. On the other hand a real fluid, in addition to the normal forces, tangential forces also occur both between layers in the fluid and between the fluid and the walls. These tangential forces or friction forces are connected to a physical property called “viscosity” of a fluid.

Now, we are starting to see the importance of these two types of fluids and how they interact in order to create the concept of boundary layer. In a ideal fluid, there is a difference in the tangential velocities on the boundary between a solid body and the fluid, in other words, the fluid slips along the side of the body. In a real fluid, because the fluid adheres to a solid wall, tangential forces do act [1].

Viscosity

This concept can be better understood with an experiment.

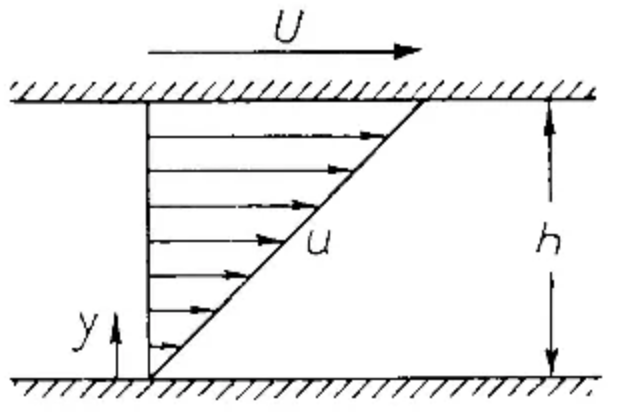

Consider the flow between two long parallel plane plates, one of which is at rest while the other moves at velocity U in its own plane. The distance between them is h. From the experiment we see that the fluid adheres to both plates so that the velocity at the lower plate is zero, while at the upper plate the fluid moves with velocity U. Therefore, there is a linear velocity distribution between the plates; so, the velocity is proportional to the distance y from the lower plate, what leads to [1]:

→ Velocity gradient

In order to maintain the state of motion, a tangential force in the direction of motion must act on the upper plate. This keeps the friction forces of the fluid in equilibrium. According to experimental results, this force (force per unit surface area of the plate = shear stress ) is proportional to U/h, and this can be replaced by du/dy. Now, the constant of proportionality between

and du/dy, which we will denote by

(which describes the internal resistance of a fluid to motion and is strongly dependent on the temperature, is called as “viscosity” of the fluid), depends on the nature of the fluid as it is a physical property. It is very low for fluids like water and air, and very large for viscous fluids like oil or glycerin.

So now, we have the elementary law of fluid friction in the form:

→ Newton’s law of friction.

Moreover, in all flows the friction forces act together with inertial forces, there’s considerable importance attached to the ratio formed by the viscosity \mu and the density \rho, denoted as “kinematic viscosity.”

→ Kinematic viscosity.

Reynolds number

After exhaustive experiments in the 1880s, Osborne Reynolds discovered that the flow regime depends mainly on the following forces: friction forces (proportional to the viscosity ()), inertial forces (proportional to the density (

)), pressure forces and volume forces (e.g. gravitational force). In other words, it depends on the ratio of inertial forces to viscous forces in the fluid:

→ Reynolds number [2]

Where is the average flow velocity, D is the characteristic length of the geometry and v is the kinematic viscosity. This is a dimensionless quantity.

At large Reynolds numbers, the inertial forces, which are proportional to the fluid density and the square of the fluid velocity, are large relative to the viscous forces, and thus, the viscous forces cannot prevent the random and rapid fluctuations of the fluid. At small or moderate Reynolds numbers, however, the viscous forces are large enough to suppress these fluctuations and to keep the fluid “in line.” Thus the flow is turbulent in the first case and laminar in the second [2].

The transition from laminar to turbulent flow also depends on the degree of disturbance of the flow by: surface roughness, pipe vibrations, and fluctuations in the upstream flow. Under most practical conditions, the flow in a circular pipe is laminar for Re ≤ 2300, turbulent for Re ≥ 4000 and transitional in between.

Boundary layer

Since many technically important fluids have very low viscosity (e.g. air or water), the majority of flows in practice are flows with high Reynolds number. Therefore the asymptotic behavior of dimensionless coefficients at high Reynolds numbers is very important. Boundary layer theory deals with precisely this asymptotic behavior. This is a theory to determine the asymptotic behavior of flows at large Reynolds numbers (i.e. Re → ).

However, the limiting case of Re → corresponds to the flow of an ideal fluid (a fluid with vanishing viscosity). Real flows have finite but very large Reynolds, numbers will then be only slightly different from this limiting case, and they can be considered to be small perturbations from the limiting case [1]. Therefore, the limiting solution Re =

is a good approximation; nevertheless, a notable shortcoming of this limiting solution is that the no-slip condition is not satisfied, i.e. the velocities at the wall are not zero but are finite. The viscosity must be taken into account in order to satisfy the no-slip condition. This takes care of the velocity transition from the limiting solution’s finite value close to the wall to the value of zero directly at the wall. At large Reynolds numbers this transition takes place in a thin layer close to the wall called by L. Prandtl as the “boundary layer” or “frictional layer,” being thinner the higher the Reynolds number (with smaller viscosity).

This concept—of boundary layer—implies that flows at high Reynolds numbers can be divided up into two unequally large regions. In the bulk of the flow region, the viscosity can be neglected, and the flow corresponds to the inviscid limiting solution—this is called the inviscid outer flow. The second region is the very thin boundary layer at the wall where the viscosity must be taken into account.

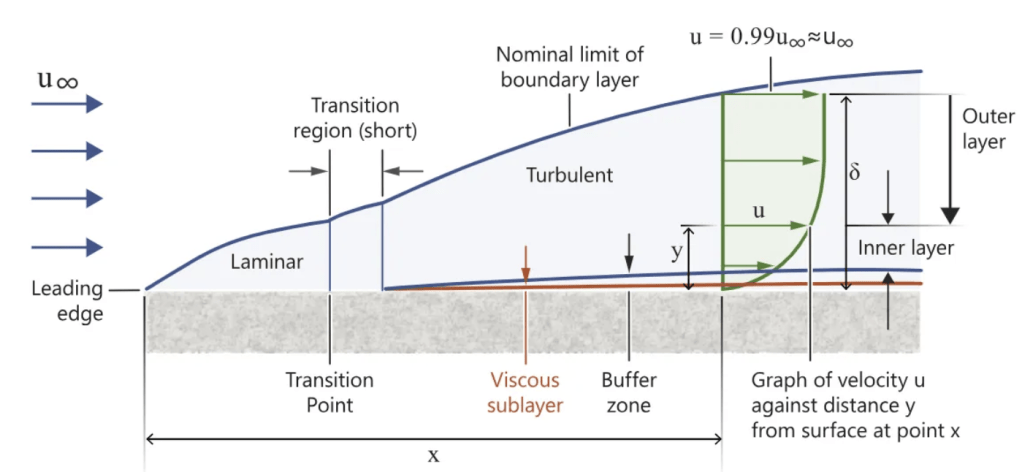

Within the boundary layer—where viscosity is taken into consideration—the two different flow forms, being laminar or turbulent. So, one then speaks of laminar boundary layer flows, and equivalently of turbulent boundary layers.

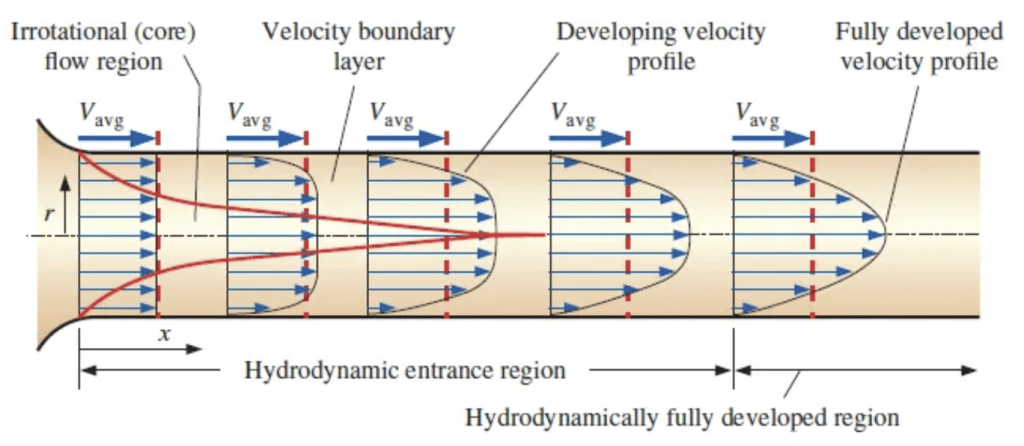

How it looks

Let’s consider a fluid entering a circular pipe at a uniform velocity. Because of the no-slip condition, the fluid particles in the layer in contact with the wall of the pipe come to a complete stop. This layer also causes the fluid particles in the adjacent layers to slow down gradually as a result of friction—but it does it from front to back, i.e. the thickness of the layer is a monotonically increasing function of x (look at figure 2). To make up for this velocity reduction, the velocity of the fluid at the midsection of the pipe has to increase to keep the mass flow rate through the pipe constant. As a result, a velocity gradient develops along the pipe [2].

The region of the flow in which the effects of the viscous shearing forces caused by fluid viscosity are felt is the boundary layer. The velocity becomes fully developed a little farther downstream. The region from the pipe inlet to the point at which the velocity profile is fully developed is called the hydrodynamic entrance region, and the length of this region is called the hydrodynamic entry length; in the same way, the region where the profile velocity is fully developed is known as the hydrodynamically fully developed region. The velocity profile in the fully developed region is parabolic in laminar flow and much flatter in turbulent flow due to eddy motion and more vigorous mixing in the radial direction.

Furthermore, generally, the boundary layer on a plate is laminar close to the leading edge and becomes turbulent further downstream. The transition from laminar to turbulent flow forms is most noticeable by a great increase in the boundary layer thickness in the wall shear stress (figure 3); in addition, in turbulent boundary layers a sub-layer known as “viscous sublayer” will be formed just at the wall and it presents the effect of viscosity and random fluctuating motion.

Conclusions

Boundary layer is one of the most important concepts in fluid dynamics as it directly influences the shapes, attachments, dynamics and applications that a fluid will cause. The boundary layer represents a fundamental bridge between the theory of ideal inviscid flow and the real behavior of viscous fluids near solid boundaries. It provides a framework for understanding how fluid velocity changes from zero at the surface to free-stream conditions away from it. Moreover, it involves the understanding of topics such as: ideal and real fluids, viscosity and Reynolds number with laminar, transitional, and turbulent flow.

As we can imagine after knowing how it makes a fluid interact between its flow and a surface, it is crucial when talking about applications like: lift in airplanes, downforce in road vehicles, heat exchangers and more. Definitely, this is one of the physics concepts that allow humans to make possible the impossible.

Sources of information

[1] Boundary Layer Theory – Hermann Schlichting.

[2] Fluid Mechanics: Fundamentals and Applications – Yunus A. Cengel, John M. Cimbala

[3] Basic Boundary Layer Theory – Melanie Blakeslee (Altair).